- Vector Index: Optimized for searching high-dimensional data (like images, audio, or text embeddings) by efficiently finding the most similar vectors

- Full-Text Search Index: Enables fast keyword-based searches by indexing words and phrases

- Scalar Index: Accelerates filtering and sorting of structured numeric or categorical data (e.g., timestamps, prices)

Supported Index Types

LanceDB provides a comprehensive suite of indexing strategies for different data types and use cases:| Index | Use Case | Description |

|---|---|---|

HNSW (Vector) | High recall and low latency vector searches. Ideal for applications requiring fast approximate nearest neighbor queries with high accuracy. | Hierarchical Navigable Small World—a graph-based approximate nearest neighbor algorithm. Distance metrics: l2 cosine dotQuantizations: PQ SQ |

IVF (Vector) | Large-scale vector search with configurable accuracy/speed trade-offs. Supports binary vectors with hamming distance. | Inverted File Index—a partition-based approximate nearest neighbor algorithm that groups similar vectors into partitions for efficient search. Distance metrics: l2 cosine dot hammingQuantizations: None/Flat PQ SQ RQ |

BTree (Scalar) | Numeric, temporal, and string columns with mostly distinct values. Best for highly selective queries on columns with many unique values. | Sorted index storing sorted copies of scalar columns with block headers in a btree cache. Header entries map to blocks of rows (4096 rows per block) for efficient disk reads. |

Bitmap (Scalar) | Low-cardinality columns with few thousand or fewer distinct values. Accelerates equality and range filters. | Stores a bitmap for each distinct value in the column, with one bit per row indicating presence. Memory-efficient for low-cardinality data. |

LabelList (Scalar) | List columns (e.g., tags, categories, keywords) requiring array containment queries. | Scalar index for List<T> columns using an underlying bitmap index structure to enable fast array membership lookups. |

FTS (Full-text) | String columns (e.g., title, description, content) requiring keyword-based search with BM25 ranking. | Full-text search index using BM25 ranking algorithm. Tokenizes text with configurable tokenization, stemming, stop word removal, and language-specific processing. |

TypeScript currently doesn’t support

IvfSq (IVF with Scalar Quantization).Quantization Types

Vector indexes can use different quantization methods to compress vectors and improve search performance:| Quantization | Use Case | Description |

|---|---|---|

PQ (Product Quantization) | Default choice for most vector search scenarios. Use when you need to balance index size and recall. | Divides vectors into subvectors and quantizes each subvector independently. Provides a good balance between compression ratio and search accuracy. |

SQ (Scalar Quantization) | Use when you need faster indexing or when vector dimensions have consistent value ranges. | Quantizes each dimension independently. Simpler than PQ but typically provides less compression. |

RQ (RabitQ Quantization) | Use when you need maximum compression or have specific per-dimension requirements. | Per-dimension quantization using a RabitQ codebook. Provides fine-grained control over compression per dimension. |

None/Flat | Use for binary vectors (with hamming distance) or when you need maximum recall and have sufficient storage. | No quantization—stores raw vectors. Provides the highest accuracy but requires more storage and memory. |

Understanding the IVF-PQ Index

An ANN (Approximate Nearest Neighbors) index is a data structure that represents data in a way that makes it more efficient to search and retrieve. Using an ANN index is faster, but less accurate than kNN or brute force search because, in essence, the index is a lossy representation of the data. A key distinguishing feature of LanceDB is it uses a disk-based index: IVF-PQ, which is a variant of the Inverted File Index (IVF) that uses Product Quantization (PQ) to compress the embeddings. LanceDB is fundamentally different from other vector databases in that it is built on top of Lance, an open-source columnar data format designed for performant ML workloads and fast random access. Due to the design of Lance, LanceDB’s indexing philosophy adopts a primarily disk-based indexing philosophy.IVF-PQ

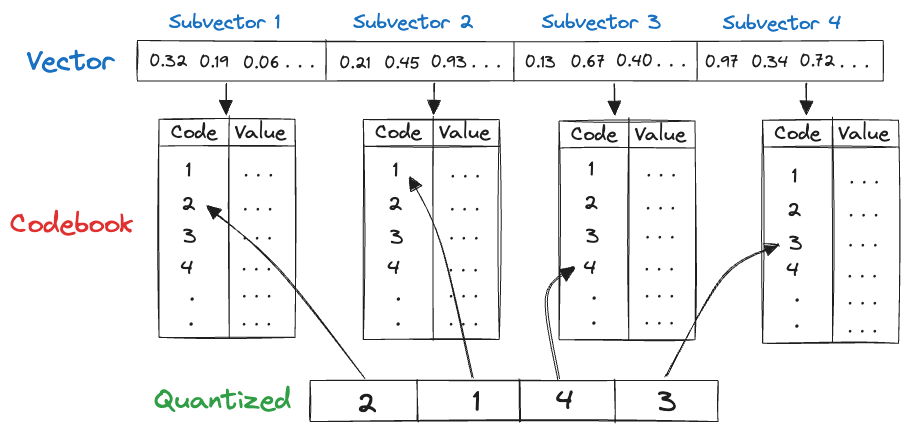

IVF-PQ is a composite index that combines inverted file index (IVF) and product quantization (PQ). The implementation in LanceDB provides several parameters to fine-tune the index’s size, query throughput, latency and recall, which are described later in this section.Product Quantization

Quantization is a compression technique used to reduce the dimensionality of an embedding to speed up search. Product quantization (PQ) works by dividing a large, high-dimensional vector of size into equally sized subvectors. Each subvector is assigned a “reproduction value” that maps to the nearest centroid of points for that subvector. The reproduction values are then assigned to a codebook using unique IDs, which can be used to reconstruct the original vector.

Original:

128 × 32 = 4096 bits

Quantized: 4 × 8 = 32 bitsQuantization results in a 128x reduction in memory requirements for each vector in the index, which is substantial.Inverted File Index (IVF) Implementation

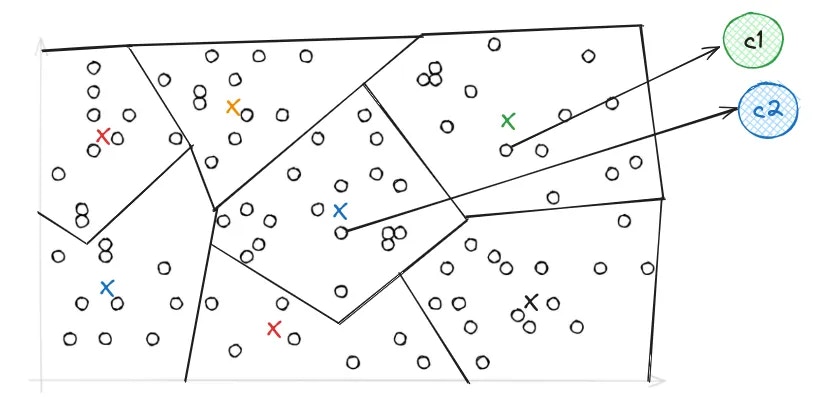

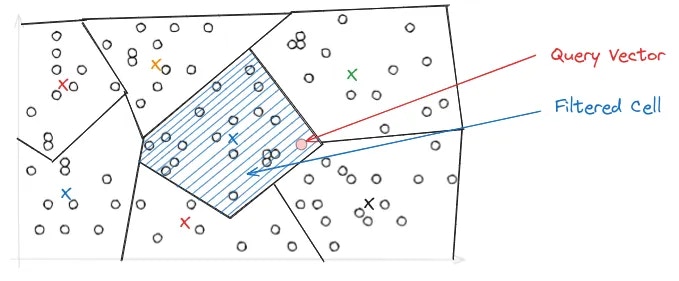

While PQ helps with reducing the size of the index, IVF primarily addresses search performance. The primary purpose of an inverted file index is to facilitate rapid and effective nearest neighbor search by narrowing down the search space. In IVF, the PQ vector space is divided into Voronoi cells, which are essentially partitions that consist of all the points in the space that are within a threshold distance of the given region’s seed point. These seed points are initialized by running K-means over the stored vectors. The centroids of K-means turn into the seed points which then each define a region. These regions are then are used to create an inverted index that correlates each centroid with a list of vectors in the space, allowing a search to be restricted to just a subset of vectors in the index.

nprobe parameter, which controls the number of Voronoi cells to search during a query. The higher the nprobe, the more accurate the results, but the slower the query.

HNSW Index Implementation

Approximate Nearest Neighbor (ANN) search is a method for finding data points near a given point in a dataset, though not always the exact nearest one. HNSW is one of the most accurate and fastest Approximate Nearest Neighbour search algorithms, It’s beneficial in high-dimensional spaces where finding the same nearest neighbor would be too slow and costly.Types of ANN Search Algorithms

Approximate Nearest Neighbor (ANN) search is a method for finding data points near a given point in a dataset, though not always the exact nearest one. HNSW is one of the most accurate and fastest Approximate Nearest Neighbour search algorithms, It’s beneficial in high-dimensional spaces where finding the same nearest neighbor would be too slow and costly There are three main types of ANN search algorithms:- Tree-based search algorithms: Use a tree structure to organize and store data points.

- Hash-based search algorithms: Use a specialized geometric hash table to store and manage data points. These algorithms typically focus on theoretical guarantees, and don’t usually perform as well as the other approaches in practice.

- Graph-based search algorithms: Use a graph structure to store data points, which can be a bit complex.

HNSW also combines this with the ideas behind a classic 1-dimensional search data structure: the skip list.

Understanding k-Nearest Neighbor Graphs

The k-nearest neighbor graph actually predates its use for ANN search. Its construction is quite simple:- Each vector in the dataset is given an associated vertex.

- Each vertex has outgoing edges to its k nearest neighbors. That is, the k closest other vertices by Euclidean distance between the two corresponding vectors. This can be thought of as a “friend list” for the vertex.

- For some applications (including nearest-neighbor search), the incoming edges are also added.

- Given a query vector, start at some fixed “entry point” vertex (e.g. the approximate center node).

- Look at that vertex’s neighbors. If any of them are closer to the query vector than the current vertex, then move to that vertex.

- Repeat until a local optimum is found.

In fact, another data structure is not needed: This can be done “incrementally”. That is, if you start with a k-ANN graph for n-1 vertices, you can extend it to a k-ANN graph for n vertices as well by using the graph to obtain the k-ANN for the new vertex. One downside of k-NN and k-ANN graphs alone is that one must typically build them with a large value of k to get decent results, resulting in a large index.

Hierarchical Navigable Small Worlds (HNSW)

HNSW builds on k-ANN in two main ways:- Instead of getting the k-approximate nearest neighbors for a large value of k, it sparsifies the k-ANN graph using a carefully chosen “edge pruning” heuristic, allowing for the number of edges per vertex to be limited to a relatively small constant.

- The “entry point” vertex is chosen dynamically using a recursively constructed data structure on a subset of the data, similarly to a skip list.

- At the bottom-most layer, an k-ANN graph on the whole dataset is present.

- At the second layer, a k-ANN graph on a fraction of the dataset (e.g. 10%) is present.

- At the Lth layer, a k-ANN graph is present. It is over a (constant) fraction (e.g. 10%) of the vectors/vertices present in the L-1th layer.

- At the top layer (using an arbitrary vertex as an entry point), use the greedy local search routine on the k-ANN graph to get an approximate nearest neighbor at that layer.

- Using the approximate nearest neighbor found in the previous layer as an entry point, find an approximate nearest neighbor in the next layer with the same method.

- Repeat until the bottom-most layer is reached. Then use the entry point to find multiple nearest neighbors (e.g. top 10).